Why Raya and the Last Dragon Is A Groundbreaking Film

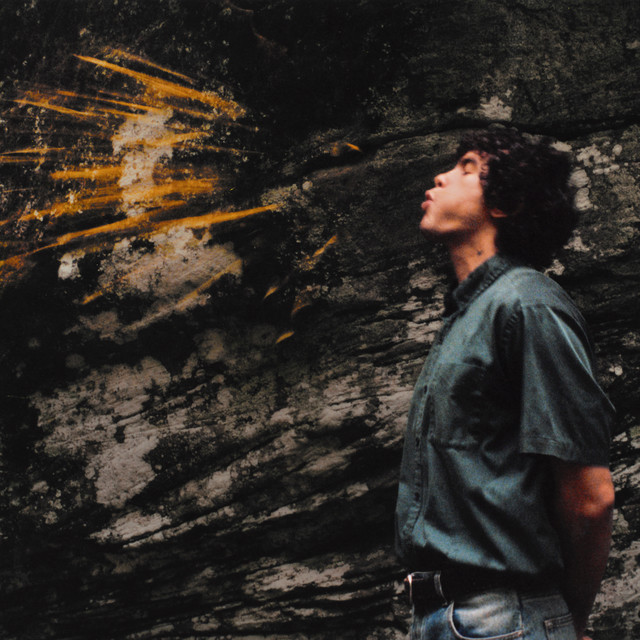

Raya, voiced by Vietnamese-American actor Kelly Marie Tran, is the first Southeast Asian Disney princess.

March 29, 2021

The Disney princess genre has come a long way since fifteen-year-old Snow White was brought back to life by the kiss of a male savior. The last two Disney princess movies, Frozen and Moana, showed signs of moving away from these old tropes, with sisterly love being key to Frozen’s climax, self-actualization key to Moana, and both Moana and Elsa’s lack of a romantic interest. Lately, Disney princesses are challenging the idea of what it means to be a princess. Raya and the Last Dragon takes these trends and runs with them.

The movie takes place in a beautifully-animated fantasy world based on the various cultures of Southeast Asia. Central to the plot is a quest in which Raya (Kelly Marie Tran), a fierce warrior, and Sisu (Awkwafina), the last dragon, must collect the pieces of a magical orb that will destroy evil forces threatening the land.

Without going into too much detail, trust is central to the movie’s theme. Trust, argues the movie, leads to unity. Characters who were hostile towards each other at the beginning of the film learn that they must put aside their differences and have faith in each other to work towards a common goal.

This message is especially poignant today, given the increasing polarization both politically and culturally in America. Raya and the Last Dragon reminds us that sometimes, to trust in our “enemies” is the best way to ensure they will place that same trust in us.

Not only that, but the movie also speaks to the current deconstruction of gender norms, as it takes place in a fantasy world where gender norms do not matter. For example, Raya’s father, Chief Benja, is one of the first positive father figures featured in a Disney princess movie, and also one who departs from the chief trope. Instead of asserting his power through brute force, Benja rules with kindness and wise practicality. “Too many men think that they need to be tough to prove themselves,” junior Avery Marchand commented thoughtfully when asked about masculinity in the media. The movie shows how beneficial a departure from toxic masculinity can be when parenting, as Benja is an excellent father who helps teach Raya many invaluable life lessons.

Raya also departs from gender norms, even more so than past Disney princesses. Unlike even recent princesses like Elsa and Moana, who have to learn to be strong and fierce, Raya seems to be born this way. She is quick to fight, aggressive, and adventurous. But, throughout the course of the movie, Raya learns to let her guard down and be vulnerable. In this way, she takes recent trends of female character growth (soft to strong) and inverts it: Raya starts her journey as a warrior but then learns that there are times she needs to give into peace and humility. Although some might think this counteracts feminist ideas, it makes Raya a more nuanced princess than ever before. Strength and toughness, traditionally masculine traits, can be possessed by anyone: shown by Raya’s natural possession of these qualities. But, princesses do not have to be tough to be powerful. Raya and the Last Dragon shows us that sometimes, letting yourself be vulnerable is even more powerful than fighting.

Representation of the LGBTQ community has been severely lacking in Disney films, so fans jumped at the sapphic undertones between Raya and her childhood-friend-turned-nemesis, Namaari. Namaari even looks queer, with her muscular build and an undercut that screams lesbian. Neither Namaari nor Raya expresses attraction to men. Although not canonically gay, many viewers noticed hints at a romantic relationship between the two women. This is no surprise, especially when Kelly Marie Tran told Vanity Fair she decided to voice Raya as though there were some “romantic feelings going on” between her and Namaari. Tran admitted that she may get in trouble for saying so, but went on to reassure fans that if “You see representation in a way that feels real and authentic to you, then it is real and authentic.” Any sequels or spin-offs that Disney might make would be a perfect opportunity to make Raya not only the first Southeast Asian princess but the first LGBTQ princess.

The sole complaint of many was the lack of authentic Southeast Asian representation in the movie’s cast. Although Disney went to great lengths to make the movie an authentic depiction of various Southeast Asian cultures, down to the weapons and fighting styles of the characters, most of the actors hired were of East Asian descent. One character even speaks with a distinctly Chinese accent. “It almost makes it worse,” says junior Helen Kahn, “knowing that they tried so hard to make it a Southeast Asian movie, but still failed with the voice actors.” This dilutes the point of representation that the film was aiming for, suggesting that to Disney, the difference between East Asia and Southeast Asia is negligible.

Disney still has a long way to go when it comes to media representation of under-represented groups. Movies like Raya and the Last Dragon may seem like harmless family movies, but these films can influence audiences’ views on things like race, gender, sexuality, peace, trust, and unity. This is why it is so important that future movies continue to advance representation in the way that Raya and the Last Dragon did so well.