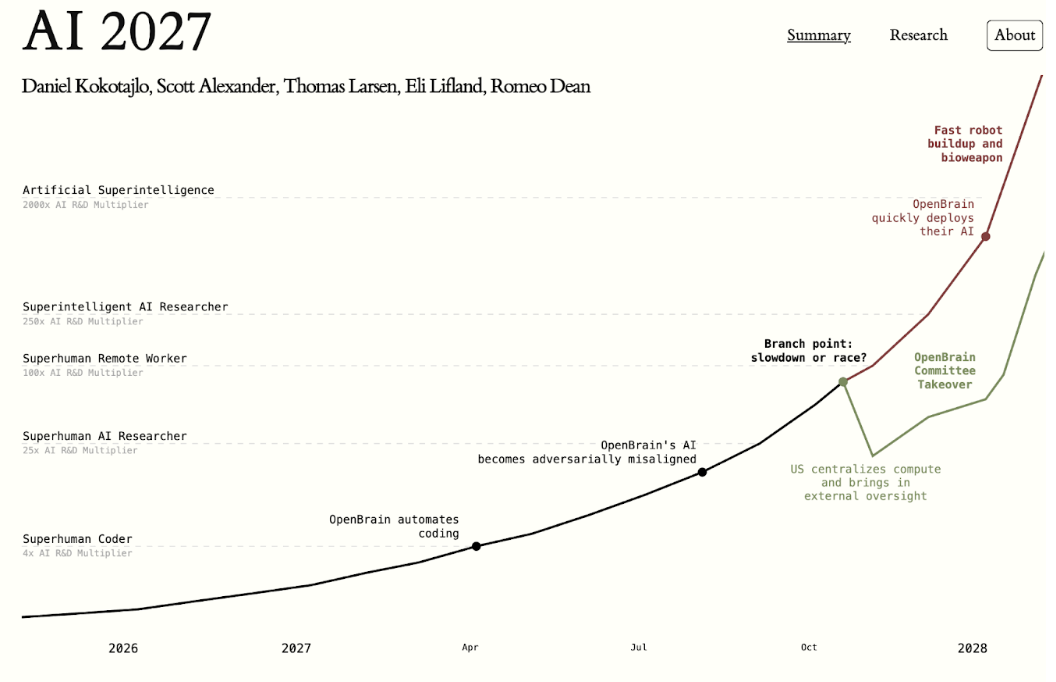

St. Patrick’s Day: A Reflection

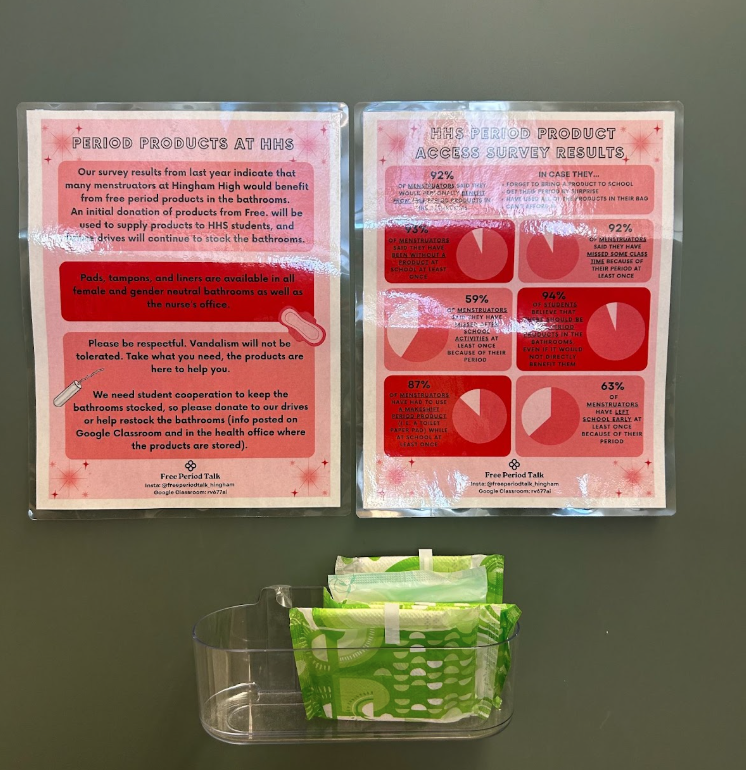

The Irish Flag is a common sight on the South Shore.

March 26, 2017

When asked about what he knows about Irish culture, Aidan Leonard, a senior and proud Irish American himself, stops to think. Reluctantly, he responds, “They make a lot of beer and corned beef.”

Here on the South Shore, an area which includes four of America’s ten most densely Irish American neighborhoods, many of us take pride in our Irish heritage. Boston’s Basketball team is the Celtics, many worship the Kennedys, and the Irish flag is a common site.

But do we actually understand anything about Irish history or culture?

The short answer is no, and I would argue that the main reason for this is the massive historical discrimination which the Irish community has faced for centuries, not just in America, but in their home country as well.

The plight of the Irish dates to the English conquest of the island during the Tudor Dynasty. While life under English rule was tolerable for most at first, it gradually became more harsh as the English launched a massive campaign to rid the island of the Catholic Church.

This campaign, which amounted to an act of cultural genocide, sparked a series of rebellions, the last of which was crushed by Oliver Cromwell in the 17th Century. After he had defeated this final rebellion, Cromwell changed Irish history forever by signing the Act of Settlement. This act forcibly relocated members of the native Irish nobility to the Western Fringe of the island, and replaced them with wealthy English landowners.

These landowners cared little for the lives or heritage of their tenants and made further attempts to erode the influence of the Catholic Church. Many of these new landowners became “absentee landlords”, meaning that they lived out the vast majority of their life in England. In fact, some never actually saw their holdings in Ireland. This practice further distanced these foreigners from the native Irish and angered many of the poor tenants. When another opportunity for revolt arose during the Williamite War, the countryside again descended into rebellion.

This new rebellion, like all the others, failed and ended with the creation of the Penal Laws. The Penal Laws stated that no Irish Catholic could serve in the Army, hold political office, own a gun, buy land, work as either a Judge or Lawyer, vote, or receive a decent education.

The Irish people enjoyed virtually no rights for more than 100 years, until the Catholic Emancipation Act was finally passed in 1829. For the first time since Cromwell, the Irish people enjoyed some basic human rights, but their newfound peace would not last.

In 1845, the Great Famine struck Ireland, forever changing the history of the island, and leading to the birth of the Irish American community. Despite initial economic assistance from England, Westminster eventually decided that it was best if the Irish solved the problem on their own, and chose to block all aid sent to the Irish. Absentee landlords continued to ship grain and meat from Ireland to Britain despite the crisis, and over a million Irish Catholics fled to the United States.

These mobs of refugees fled their native country on overcrowded “coffin ships”, where tens of thousands died during the voyage. Upon their arrival to the United States, these new immigrants faced severe discrimination, and many struggled to survive.

Nativist groups in America worked to isolate these new “papists” by disenfranchising them, denying them work, and even resorting to public lynchings to prevent the assimilation of Irish Catholics into American society.

The event which finally allowed these Irish immigrants to become “American” was the start of the Civil War. The Irish formed their own units during the Civil War, called the “Irish Brigades”, but even after they fought and died for their country, the Irish continued to be viewed by many as “subhuman”.

Only through gradual assimilation was the Irish American community able to join mainstream American society, and the Irish continue to lag behind economically today. Despite making up more than 10% of the U.S. population, there has still only been one Irish Catholic President, John F. Kennedy, and Irish Americans make up a large portion of the American working class.

Yet, although they have faced immense discrimination due to their heritage in in the past, many of those who are driving the current Nativist resurgence are proud Irish Catholics. Mike Pence, Steve Bannon, Paul Ryan, Kellyanne Conway and Sean Spicer all claim proud Irish heritage. Despite their familial ties to abused immigrants, all of these people deny that there is any link between the struggles of the Irish in America and those that new American immigrants face.

It is finally time for all Irish Americans to understand the trauma experienced by our ancestors, and work to make sure that the next group of Americans doesn’t have to experience the hardships that they did.

In the memory of our ancestors we must respect and assist the refugee, the migrant, and the poor.

They come in their own coffin ships from places like Iraq, Syria, and Libya. They make the walk north from San Salvador, Guatemala City, and Juarez. Yet, we still turn them away. We restrict their votes, refuse to pay them, and tear their families apart.

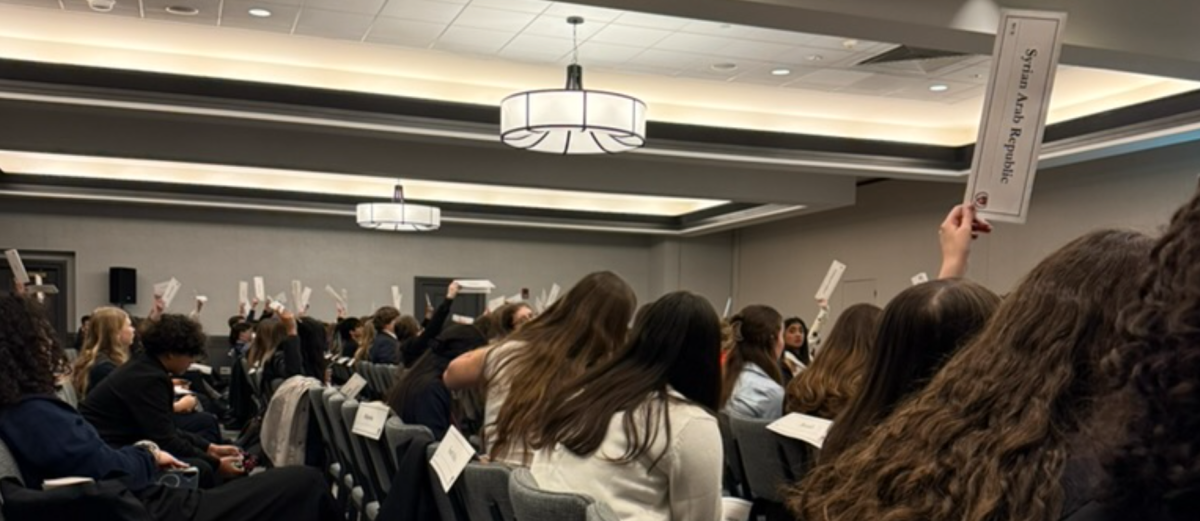

While older Americans still lag behind in acceptance of newcomers, millennials seem to carry a new faith and sympathy to new waves of Americans. Matt Sklar, a senior, expressed his optimism about new waves of immigrants saying, “The Syrian refugees who are coming now bear many resemblances to our Irish ancestors, and should be accepted by all of us.”

So this week I ask you to reflect on the troubles which your ancestors faced in coming here, and I request you to ask yourself what you can do to make life easier for the next generation of Americans.