A Meeting with Lech Wałęsa, Former Polish President

Student Foreign Correspondent Claire Taylor Shares her Experience

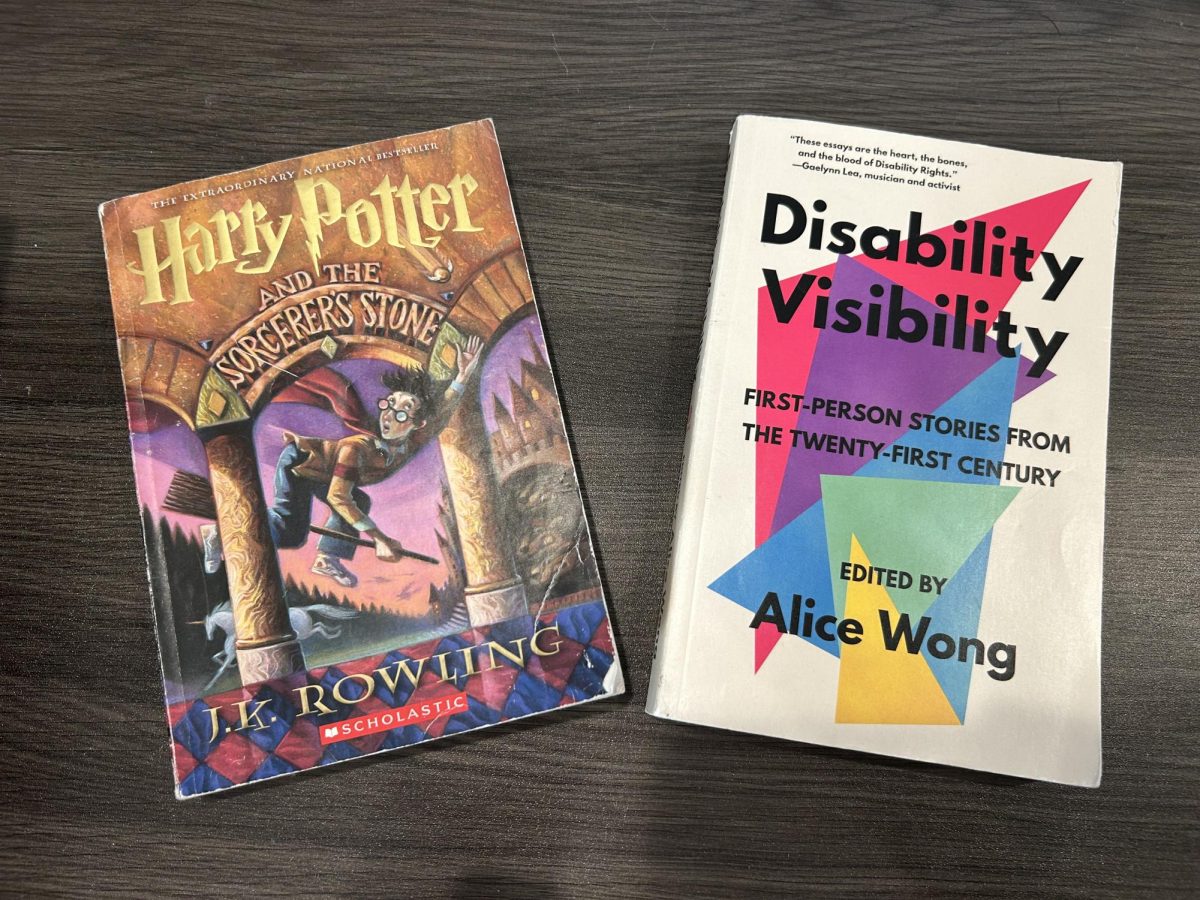

Courtesy Wałęsa’s security guard

From left to right: Claire Taylor, Lech Wałęsa, Tomasz Taylor.

May 10, 2017

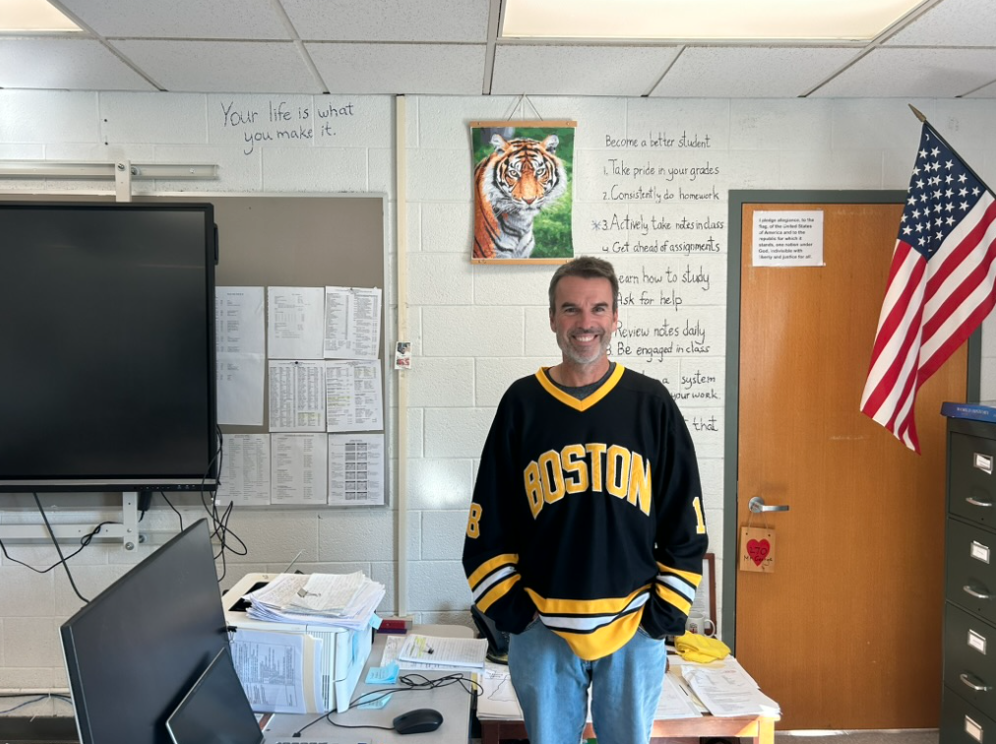

Former Polish President Lech Wałęsa shakes my hand on the second floor of the Solidarity Museum somberly. He is dressed in black, worn looking pants, a dark shirt and textured suspenders. The former President looks more like a farmer than the icon who brought down communism in Eastern Europe and dismantled the Iron Curtain. Our meeting is arranged by my uncle, Jacek Taylor, who fought side by side with Wałęsa during the Solidarity Movement in Poland. Despite Wałęsa’s casual attire during our meeting, as always, the rectangular Holy Mary badge that possesses a white and red background to resemble the Polish flag is pinned to the left breast pocket of his shirt. His expression is gloomy and unenthusiastic as he quickly asks me to sit at the table beside him and begin the interview.

It has been thirty seven years since Wałęsa founded Solidarność, or Solidarity, the movement that made a major contribution to defeating communism in Eastern Europe. At seventy three with white hair and a mustache, he looks unlike the iconic 80s images that the world recognizes. I was fortunate enough to meet this legendary man due to my uncle’s long friendship with Wałęsa since 1970, when they experienced the trials and tribulations of fighting for freedom from communism in Poland together.

Growing up in the United States with a father who grew up in communist Poland, Wałęsa was not a household name. This is partly because I had not yet studied the Cold War in school and partly because the way that Americans pronounce “Wałęsa” differs extremely from the way Polish people pronounce it (va-wen-sa). I learned of Wałęsa and my family’s connection to him and Solidarity while studying abroad for sophomore year in an American high school in Warsaw where my father’s family resides. For the interview, we sat in Wałęsa’s office where the windows overlook the shipyard, the starting line for Solidarity.

Wałęsa arrived as an electrician in Gdańsk searching for work in 1969. During this time in Poland and all across Eastern Europe, working conditions were deplorable and food was often scarce. After being hired and fired multiple times and viewing the obvious problems that haunted the shipyards and workplaces, Wałęsa concluded that change was needed. Many others saw the horrors and thought about change, but Wałęsa spoke up first. This began with a strike to increase the wages of workers in the shipyard.

When I asked at what exact moment he knew this change in wages was necessary, Wałęsa responded that it started at birth. “I fought since I was born,” he said. “Anti-communism came in the breast milk of my mother. I would say that I fought against communism since I was a child, in various ways. When I grew older, I gained more influence and had more opportunities until we got to the stage of the shipyard. I was fighting in the shipyard for 10 years before August 1980 [the strike in Gdańsk that demanded the legalization of free trade unions] and I was losing.”

In 1980 during the strikes, round table talks were also held between the strike committee headed by Wałęsa and communist Polish government representatives. Ultimately, the strike committee won against the communists. I asked Wałęsa at what point he knew that he was going to win. “Until the end, I was thinking that it would take more time,” he said. “I thought that this victory would not be the full victory.”

During this time, Wałęsa was communicating with Václav Havel, a Czech playwright who was fighting communism in Czechoslovakia at the time, because of fear that Solidarity would not win against communism. “We were talking with Havel because we thought that after our Solidarity, if we were going to lose, we would continue fighting together with international Solidarity of Central-Eastern Europe that we wanted to form. But, we won in Poland.”

Like any historical cause, freedom came with a price. By 1981, Solidarity was growing in popularity in Poland and attracting global attention rapidly. Soviet forces feared their power was slipping. On December 13, 1981, with Soviet troops on the Polish border, martial law was declared by Prime Minister Wojciech Jaruzelski and lasted until July 22, 1983. During these two years, Wałęsa was kept under house arrest and my uncle remained in hiding in his mother’s basement in order to resist arrest. Solidarity was declared illegal during martial law. Despite setbacks, Wałęsa continued to pursue the movement for freedom.

I asked him how his spirit was not broken in such seemingly bleak times for Solidarity. “I was the leader,” he said. “I had to believe in success and at the same time handle all surprises. Actually, I was most prepared for the martial law. I knew that communists were going to strike us. I knew that we can’t give up. We could not face them with arms because they were stronger. We thought that even if you [communists] lock us up, at some point you will set us free, but then we won’t work for you anymore.” He claimed that the Polish people had “enough of communism, so you [communists] work on your own but we, the working people, we won’t work for you anymore. That’s why for the leader, if this were not to be a victory, the next one would be a victory.”

Eventually, with willpower and perseverance, freedom from communism won in Poland. This liberation was marked with the holding of free elections in 1990 in which Wałęsa was elected the first president of free Poland since before both world wars. I asked why Poland was indeed so special that the fall of communism sprouted here and not in any other country within the Soviet bloc. “We [Poles] have more than a thousand years of history with wars, battles, fights and armed uprisings, actually many of them against Moscow,” Wałęsa said. “At the same time, we have the Baltic Sea,” He nodded towards the shipyard outside the window. “Many people were always coming here… active people who were oppressed elsewhere were coming to Gdańsk. So the climate here was ripe for a revolution.”

United Europe has made an incredible impact on Poland and many other countries in Europe. Wałęsa said that a united Europe is needed “for a very simple reason. I am an electrician, a blue collar worker [he used the specific word robotnik in Polish], so I look at the world in a very practical way,” he said. “After we invented airplanes, internet, satellite TV, there is not enough space in our countries and states, so we have to create something bigger. We have to create the state of Europe.” He then connected the importance of technology in shaping the future of Europe. “There must be places, offices, to do common business. All this is necessary because of the progress of civilization and technology. Technology requires bigger space, structures and programs.”

For the world, Wałęsa became an inspiration as an unexpected symbol of hope and justice for common people. Particularly, he became an icon among the youth. I asked him what he says to the the next generation of American, Polish and international young people. “In the relay of all generations, you have the best shot for peace, development and prosperity. But you have to keep in mind that all what we have built so far: structures, states, programs, are outdated and do not fit into modern times. You have to correct them and adjust to new times. The faster and more efficiently you do it, the better for all mankind and a bigger victory for yourself.”

In textbooks, Wałęsa’s accomplishments of the Nobel Peace Prize of 1983 and his presidency from 1990 to 1995 are presented. Still, when asked what was the happiest moment of his political career, Wałęsa says, “I am still waiting.”

After our meeting, I thanked Wałęsa wholeheartedly. He quickly nodded as if he wasn’t listening and insisted on taking photos. My uncle warned me that he loves taking photos. Wałęsa went to a back room and pulled out a formal dress jacket, still with a Holy Mary pin on the left breast pocket, and pulled it over his shirt. We sat back down at the table. Wałęsa placed his hands palms down on the table. I held mine in my lap as his security guard flashed the camera. Wałęsa posted the photo on his Facebook page excitedly, signed autographs with a quick scribble, and went on with his day.

Awe kicked in only hours after I left the museum. The man spoke with coherency and precision that cut slick like a sword. His responses left me with concise but intriguing answers. No pauses, looks to the ceiling or fragmented sentences.

However, what struck me the most out of this day was that a seventy three year old man with a white mustache and white hair spoke for modernization. At this point in time, it seems to have become almost common when turning on the TV and seeing men with white mustaches and groomed hair, similarly to Wałęsa’s appearance, that they will attempt to persuade their audiences to apply past policies to the future, not speak for new thinking or construction. Wałęsa spoke for the exact opposite.

For the world, Wałęsa’s character lives on in memory of reconnecting continents after decades of high tensions between East and West and restoring human rights in the East. In Gdańsk, where the once noisy shipyards remain silenced, he lives on as a symbol of hope and as an example of the power of speaking out for equity.