Boston Abolition and Black History Tour: A U.S. History Field Trip

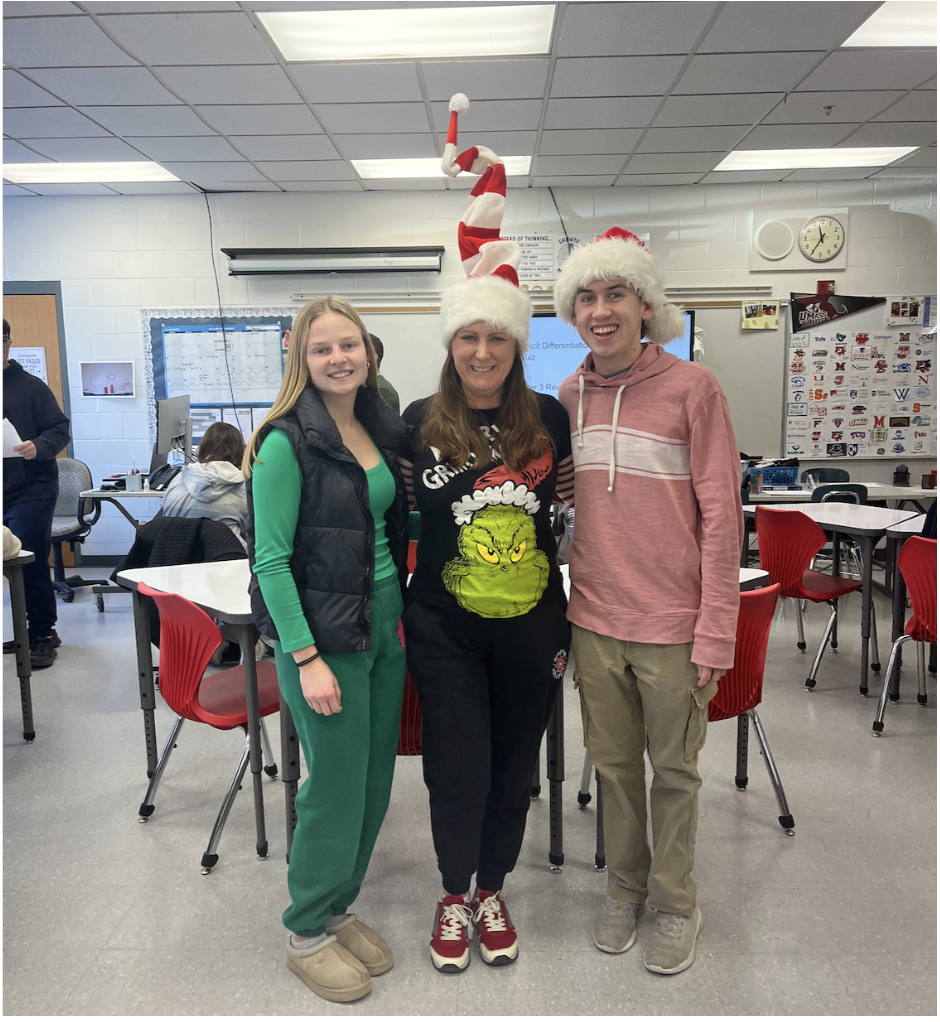

Ms. O’Connor’s class walking down Beacon Hill (before the rain).

October 29, 2017

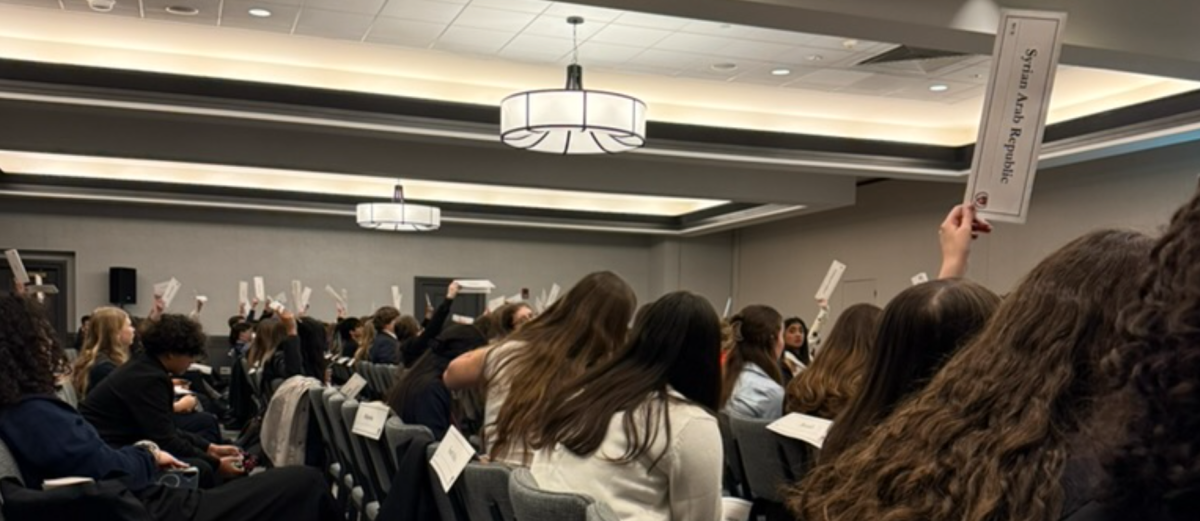

This Wednesday, October 25, Ms. O’Connor’s AP US History class travelled to Boston for a walking tour of the city, led by author Kevin Levin. The tour centered on black history, specifically the abolition movement in Boston, with a strong emphasis on analysing the way in which Bostonians chose to remember their history.

As preparation for the tour, the class read an article about some of the controversy and conflict in South Carolina concerning Confederate monuments, and students wrote down their thoughts or questions. Therefore, despite the rainy weather, the class was looking forward to the trip. Junior Nicholas Sullivan said “I’m really excited for the trip, I think it’s going to be cool.”

The class first stopped outside Boston’s historical African American Meetinghouse, which has now been converted into the Boston and Nantucket branch of the Museum of African American History. The large brick building is tucked away among side streets and brownstones in the affluent Beacon Hill neighborhood. Here, the class learned that from the 1830s to 1890s the back of Beacon Hill was the African American hub in Boston.

However, as the city grew, Beacon Hill became prime real estate, and enterprising whites quickly pushed out African Americans. Junior Ava Barzouskas felt shocked by this, and responded that “I used to live in Beacon Hill and it’s really surprising that just a few streets away black people used to live there, but they were pushed out.. There’s a whole other history [there].”

After trudging back up Beacon Hill, the class stopped at the Robert Gould Shaw Memorial; this monument memorializes the 54th regiment of Massachusetts. The 54th was the first black infantry during the Civil War. The monument depicts Colonel Shaw, on horseback, leading his men down Beacon Hill to their ships.

Mr Levin explained that many view the monument as racist because it depicts Colonel Shaw, a white man, literally higher (on horseback) than the black soldiers. Levin countered this argument by explaining the monument’s history. The artist, Saint-Gaudin, worked for nearly twenty years before unveiling the relief sculpture in 1897. Each of the black soldiers were modelled by real people for Saint-Gaudin. At the time, depictions of African Americans usually were not accurate, and very derogatory.

In addition, the sculpture was the first monument commemorating black soldiers in the civil war, and remained the only monument of its kind until 1998. At this site, Levin explained to the class that Massachusetts black soldiers refused to accept their salary, because it was lower than that of a white soldier, and many fought without pay.

As the class moved on to the statues in the Boston Public Garden of prominent abolitionists, Levin pointed out that there are no monuments for black abolitionists in Boston. This further developed the class’s discussion about the way people chose to remember history. Bostonians tend to think of themselves as particularly abolitionist and egalitarian, but, in truth, many of Boston’s early prominent families built their wealth on slavery.

The tour further clouded the class’s view of Boston with the controversial Emancipation Memorial (1876). The statue, which has its own square complete with granite seats and a small area of grass, depicts an erect Abraham Lincoln, holding in one hand the Emancipation Proclamation, and gesturing towards a kneeling, chained, slave with his other hand. Opinions were very mixed.

Junior Molly Schwall thought that “When I first saw it I was like, ‘Oh, that’s bad,’ but then I showed it to my dad who pointed out that Lincoln’s arm are kinda opened to the slave, as if saying, stand up, you’re no longer a slave.” With controversy and varied opinions on their minds, the students then went to Chinatown for lunch.

Everyone enjoyed the experience, and lots of people tried new foods that they would not have tried otherwise. As the class discussed their experience this Friday, a connection between lunch and the tour formed. In the last 10-15 years, Chinatown has begun to slowly shrink, and give way to highrise elites, just as the elite once swallowed the historically black Beacon Hill. Bostonians remember a whitewashed abolitionist history, which begs the question: how will cultures be remembered in the future?