Op-Ed: What Constitutes a National Emergency?

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi of California, alongside Rep. Joaquin Castro of Texas, left, as well as others, speaks about a resolution to block Trump’s national emergency declaration.

March 2, 2019

A declaration of a national emergency is not something to be taken lightly.

From the time U.S. presidents initially garnered the ability to call national emergencies, a total of 58 have been declared over the years. Every president since Jimmy Carter has called for at least one, many of which have been revoked by now. A common theme among these national emergencies is that most of them concern international affairs, such as when Carter called a national emergency regarding the Iran Hostage Crisis. However, some of these emergencies have been domestic; on October 23, 2009, Obama declared a state of emergency after over 1,000 Americans died from the swine flu.

Before the February of 2019, Trump had only declared three states of emergency. On December 20, 2017, Trump imposed sanctions against those involved with Myanmar’s Rohingya conflict. On September 12, 2018, he declared that sanctions would be automatically imposed in the case of foreign interference in U.S. elections. On November 27, 2018, he called for an emergency in response to the human rights violations committed by the Nicaraguan government. All of these issues pose significant threats to the wellbeing of innocent people, both in the U.S. and abroad.

But now, as of this month, Trump has abused his power by calling a national emergency to fuel his desire to secure funding for his border wall.

Before diving into what Trump’s actions mean, it is important to first understand what a state of emergency actually is. When something occurs that the president deems a crisis, he can call a state of emergency, which empowers the government and the president to act in manners they are not usually permitted to; essentially, the president is capable of effectively lessening the limits of his own authority. The idea is that, in crisis, the government’s ordinary proceedings are insufficient to face the issue at hand. The idea is that the president will only manipulate such power when a truly dangerous threat exists. This is not what Trump has done.

Senator Kevin Cramer, a North Dakota Republican, is one of few futilely attempting to defend Trump’s faulty national emergency. Cramer claimed, “Barack Obama declared a national emergency to fight swine flu and we didn’t have a single case of it in the United States.” Clearly, this is far from the truth. But it seems more than plausible Cramer is simply turning to Republicans’ frequently used tactic of pointing fingers at Obama in the attempt of painting Trump in a more favorable light.

According to the Oxford Dictionary, an emergency is defined as “a serious, unexpected, and often dangerous situation requiring immediate action.” Nothing about illegal immigration poses a dire threat in need of an urgent response; in fact, illegal immigration along the southern border is even less of a problem than it has been in the past. According to Border Patrol apprehensions data, the amount of illegal entries into the U.S. from Mexico has seen more than a 90% decline since the fiscal year 2000. The Center for Migration Studies recorded that the undocumented population in the U.S. fell from 11.7 million in 2010 to 10.7 million in 2017. That 10.7 million comprises less than 4% of the total US population. To put it simply, illegal immigration is by no means an emergency.

But not only are there fewer undocumented immigrants in the U.S. than there were before Trump’s presidency even began, they do not represent the threat to Americans’ wellbeing that the Trump administration wants people to believe that they do. In the fiscal year 2018, ICE arrested 105,140 immigrants, but many activists point to the possibility of ICE inflating these statistics by including minor charges such as traffic offenses in their numbers. In fact, an article by The Washington Post from January of this year details the numerous ways in which the Trump administration utilizes inflated numbers to confirm its anti-immigrant sentiments.

Additionally, although Trump and his administration adamantly assert that immigrants are an overwhelming criminal presence in America, worthy of instigating a national emergency, this too is an exaggeration of the facts: less than 6% of the entire state and federal prison populations of the U.S. is composed of noncitizens. Moreover, the Bureau of Justice Statistics, which provided this percentage, mentioned in a report that different prison jurisdictions classify “noncitizens” in different ways. For example, some areas base the statistic solely off of where an inmate was born regardless of whether or not he or she has received citizenship status between birth and incarceration. Not only this, but many of the immigrants imprisoned in the U.S. are in jail for very immigrant-specific crimes that do not apply to the general population. “The vast majority of immigrants in federal prison are there for crimes that only immigrants can be charged with — illegal entry and illegal entry after removal,” specified Tom Jawetz, the vice president for immigration policy at the Center for American Progress. “When you cook the books you shouldn’t pretend to be surprised by the results.”

In a 2015 study conducted by the Cato Institute, it was found that the immigrant rate of criminal conviction and arrest was actually well below the native-born rate of criminal conviction and arrest. Evidently, immigrants do not commit as many serious crimes as Trump and his administration suggest, and they certainly do not necessarily pose more of a threat than the average U.S. citizen.

However, regardless of these statistics, the biggest issue is why the national emergency was actually called: as Trump threatened during the government shutdown, this “emergency” was declared over the lack of funding for the wall Trump promised to build back during his 2016 campaign. First he asserted Mexico would pay for it. When that failed, he tried to force the United States to do so. And now that Trump is facing the resistance that his opposers always promised he would, he is desperate to fulfill the promise he made, not just for his supporters, but, more than anything, for himself.

Sure, Trump has delivered on some of his campaign pledges, such as when he rejected climate change by pulling out of the Paris climate agreement and nominated a conservative justice, who turned out to be Brett Kavanaugh, to the Supreme Court. Others, however, not so much; he never did “lock [Hillary Clinton] up,” he rescinded his assertion that China is a “currency manipulator,” and he abandoned his support for torture after claiming he would “make it… much worse” because “torture works.” But one of the biggest rallying cries that surrounded his campaign was “Build the Wall,” and it remains unfulfilled. Clearly, Trump is not beyond abusing his power to make it happen.

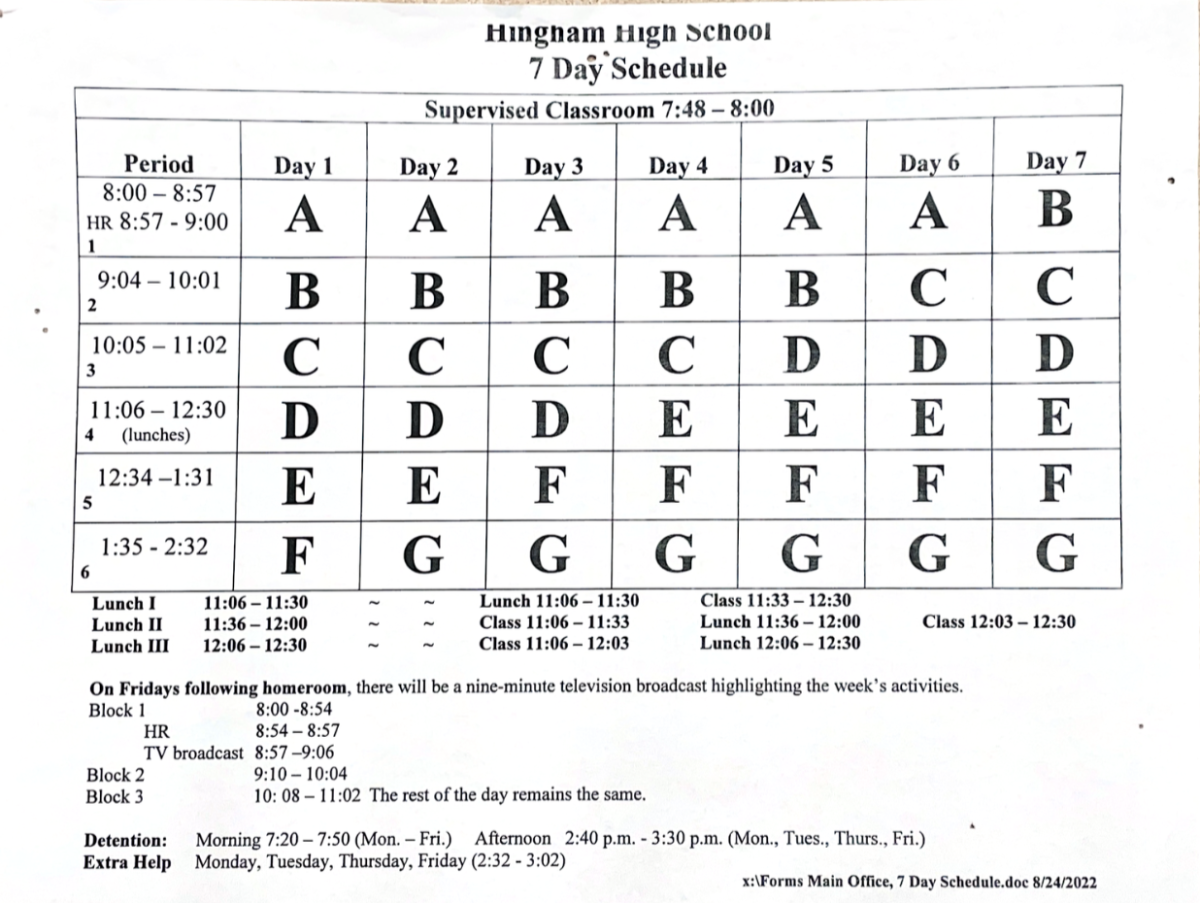

But do not just take my word for it–even the government is fighting back. On Tuesday, February 26th, the House, which has a Democratic majority, voted 245-182 to pass a resolution aimed at overturning Trump’s national emergency, according to CNN. Despite the Democrats having the House, thirteen Republicans voted alongside them to pass the resolution. Also on Tuesday, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell revealed that, even after he met with Vice President Mike Pence, he still is not sure if Trump’s national emergency is legal, according to The Washington Examiner.

Furthermore, the House is not alone in its disapproval; the Senate, which has a Republican majority, has urged Trump to call off his national emergency unless he wants to face pushback from the GOP. Three Senate Republicans have already stated that they will side with the Democrats in voting on a resolution to overturn the emergency. The Senate would only need one more Republican’s support to successfully block Trump. Ten other senators have expressed that they want to block the president’s action or that they are considering doing so.

Senator Lamar Alexander, a Republican from Tennessee who is one of the ten senators mentioned above, explained, “[Trump’s] got sufficient funding without a national emergency, he can build a wall and avoid a dangerous precedent.”

Party lines should no longer matter when a president blatantly abuses his authority; recent events such as this and Michael Cohen’s testimony have begun to prove that the law is and should be treated as bipartisan. A national emergency should only be called when innocent lives and livelihoods are truly and undeniably at stake in some way, requiring immediate action–not when a president fails to come through on a campaign promise. Especially when a national emergency can be misused as a gateway to increased power. Cohen gave a foreboding warning during his testimony, which is one that should not be ignored: “I fear that if [Trump] loses the election in 2020, that there will never be a peaceful transition of power.”