My Global Citizenship Program Project: Le Figaro

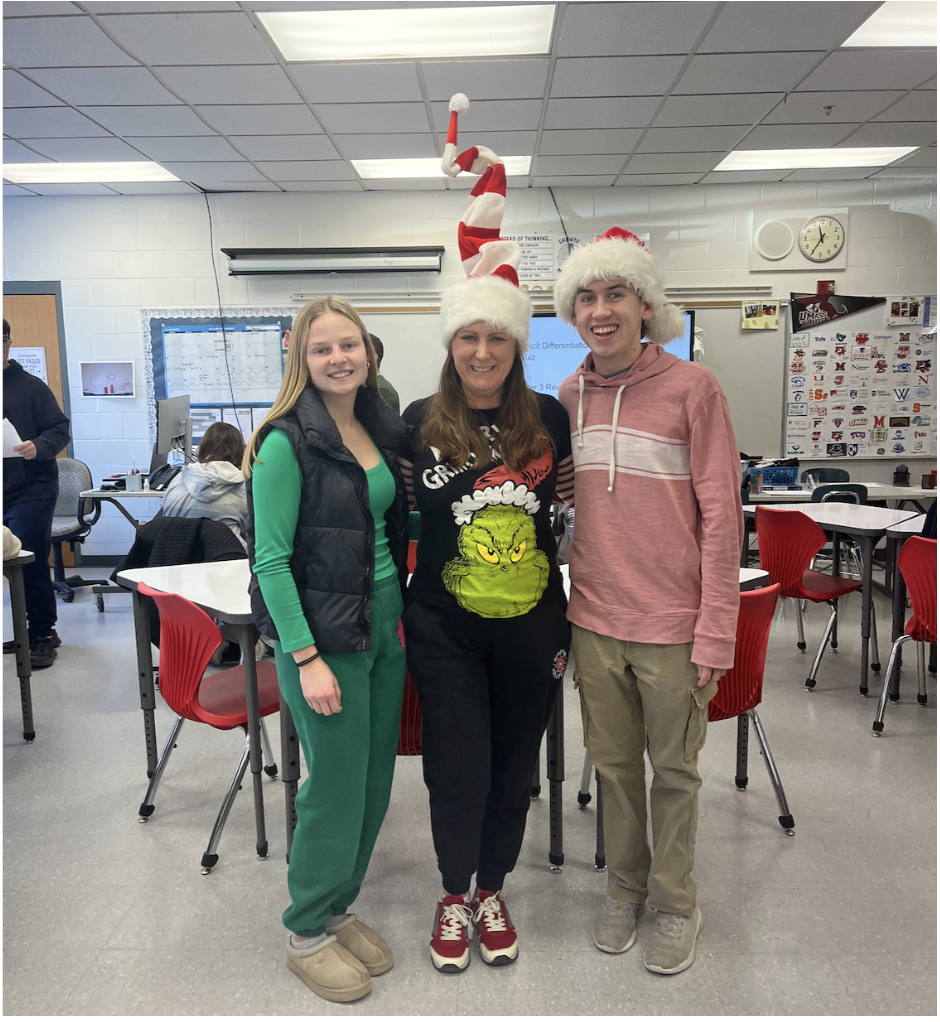

My copy of Le Figaro.

December 31, 2019

This article is the second piece of a five part series that will be featured on the Harborlight during the 2019-2020 school year and will serve as the “Creative Exploration” requirement for the GCP Portfolio.

In the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo Attacks in 2015, France has experienced very few shootings or attacks targeted at members of the press. Nevertheless, most French publications remain reluctant in having media directly interact with protests and inserting reporters on the frontlines of newsworthy activity. A family friend recently traveled to France and purchased a copy of Le Figaro, a popular French publication, which I analyzed in order to search for trends regarding the recovering state of freedom of the press.

During the French Revolution, Pierre Beaumarchais famously delivered a monologue titled “Le Mariage de Figaro,” which attacked the French crown for limiting freedom of the people and democratic principles. In the monologue, Beaumarchais states, “sans la liberté de blâmer, il n’est pas d’éloge flatteur,” which roughly translates to, “if there is no freedom to criticize, praise can not be taken seriously.”

The first thing that caught my eye when I first looked at the copy of Le Figaro was that famous line, which is located directly under the publication name. After research into the history of “Le Mariage de Figaro,” I realized that this publication aims to encourage freedom of the press, as it is one of the democratic principles that was gained after the French Revolution. Le Figaro actually further promoted this slogan after the Charlie Hebdo Attacks with the motive of reminding the country of the long history that granted the country freedom of the press after such an attack on one of these principles that the country fought for.

The headlining article for the paper is about Russian gulag children and their “last fight.” The article shows a photo of a child on the frontline of the event. The reporter also interviews children directly impacted by the event. I was surprised to see just how close to the frontline the journalist was, as this contradicted the trend that I witnessed in Paris, as reporters tended to distance themselves from the center of the story.

However, as I looked through the paper even more, I realized that very few stories addressed problems in countries other than France. I conducted more research on the publication, and realized that although it considers itself to be a global publication, it rarely attacks issues other than those in France. Nevertheless, the headlining article had nothing to do with national affairs.

Considering the tendencies of the press that I witnessed while in Paris, it is possible that the press tends to back off of the local events due to fear of local objection, as such interaction with French populations resulted in the Charlie Hebdo Attacks, as a group felt offended by the press’ interpretation of national events. However, when covering international events, the press does not have to fear local objection, as the coverage likely does not include or reference local populations.

Of course, Le Figaro still emphasizes the value of the freedom of the press in its slogan and in its name, yet tends to back off of the frontline, as most French publications tend to do, in the wake of such an attack on the freedom of the press. Without freedom of the press engrained in national legislation, the publication relies on its roots in order to preserve and encourage the continuation of this journalistic principle.