Man wrongfully imprisoned for 15 years tells his story

May 20, 2018

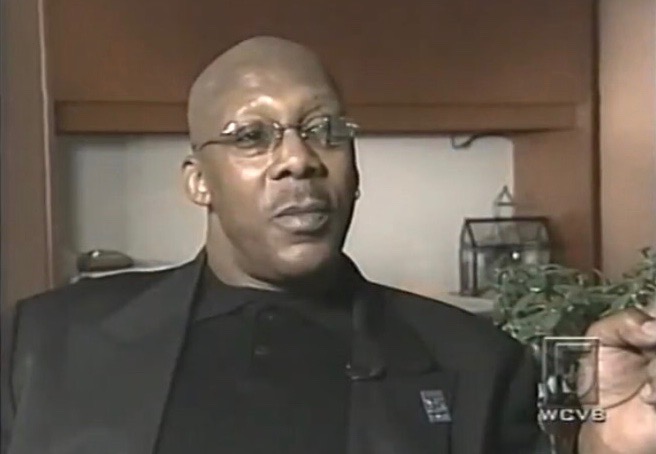

On May 15, 2018, Hingham High students gathered in Room 103 to listen to Bobby Joe Leaster tell his gripping story. In 1970, Leaster, a 19-year-old black man, was wrongfully arrested for the murder of Levi Whiteside, a white man. In 1971, Leaster was subsequently convicted for the crime he did not commit, and served time for this crime until 1986.

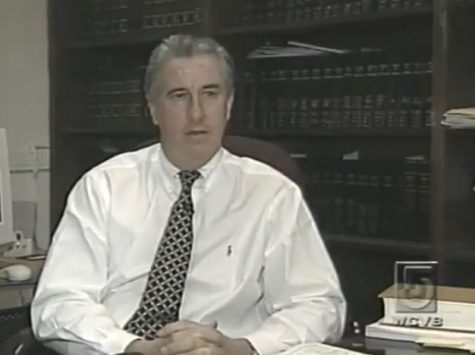

Accompanying Leaster to HHS was Chris Muse, a Hingham father as well as a justice in superior court. After Leaster spent 15 years in prison for a crime he did not commit, Muse was the lawyer who secured Leaster’s release.

At the start of the event, Principal Swanson introduced Bobby Joe Leaster and Chris Muse, noting that Room 103 was “filled to capacity” because of the interest shown by so many Hingham students and staff members. After these introductions, Chris Muse approached the podium to give some introductions of his own.

Muse explained that he had started off his career as a teacher for 7 years before becoming a lawyer, which is when he stumbled upon Leaster and Leaster’s unjust conviction. After his time as a lawyer, Muse became a justice, a role in which he has served for the past 17 years.

“One of the nice releases of my job is to be able to go out and speak to community groups and especially student groups…I really like being here with you,” he shared, addressing the crowd of students before him. Muse then began speaking of Leaster and the crime Leaster was wrongfully convicted of.

For the past 28 years, Leaster has served as a street worker, dedicating his life to supporting and helping the at-risk communities of Boston. Muse described that Leaster is “deep within the toughest communities in Boston, with the most at-risk children. He is in the middle of the chaos that [HHS students] are lucky enough just to read about.”

Those words spoke to the kind, giving qualities of Leaster, making the struggles he had endured seem all the more upsetting.

Muse also spoke a lot to the value of the rule of law, emphasizing the crucial importance of regarding every single person as equal before the law. He highlighted the necessity of knowing your rights. He talked about the mere beginnings of the due process of law, as protected by the 5th amendment, which came to be through people and events such as John Adams, the Boston Massacre, and the Declaration of Independence.

Muse cited the revered line of the famous Declaration, “We hold these truths to be self–evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” as what he dubbed “probably the most important sentence ever.”

After drawing the audience’s attention to the severe importance of due process and equal treatment before the law, Muse delved into all the ways in which Bobby Joe Leaster was unlawfully denied these rights back in 1970.

“My dear friend of 40 years, Bobby Joe, was not treated equally before the law… Things such as his race, things such as disenfranchisement, public attitude, and prejudices were all part of the reason that this beautiful man,” declared Muse, motioning to Leaster, “served 16 years for a crime he did not commit.”

Back in 1970, Muse explained, a woman named Mrs. Whiteside was working at her and her husband’s store in Roxbury when two or possibly three gunmen attacked the store. Mrs. Whiteside screamed for her husband Levi Whiteside, who entered the scene and broke a coffee mug over the head of one of the robbers. In retaliation, one of the robbers shot and killed Mr. Whiteside.

Muse said that Mrs. Whiteside told the police that her and her husband’s attackers were “two unknown colored males, 6 feet tall… both dirty looking and needing shaves.” Further, at least one of the attackers would have needed to show some sign of injury after having the coffee mug smashed over his head. Muse paused here, putting his arm around Leaster and facing the crowd in order to declare that Leaster, by no means, matched that description.

However, Mrs. Whiteside also identified one of the attackers as wearing green pants and a black shirt. Unfortunately, Leaster did match that part of the description. The cops spotted Leaster in these clothes in the South End of Boston that day.

Despite it being improbable that Leaster had fled the scene in Roxbury, somehow managed to make it over to the South End extremely quickly, and then decided to take a stroll through the city, the policemen saw Leaster’s clothes and dark skin and immediately arrested the innocent, 19-year-old.

“It would be like if a cop came here now and arrested you guys for a crime in Weymouth,” Muse clarified, relating the ludicrousy of the occurrence to the students before him.

The investigations that followed were just as unfair as the initial arrest. When Mrs. Whiteside saw Leaster, she identified him as the attacker. However, Mrs. Whiteside was hysterical after the murder of her husband and that day alone she had already been sedated twice, making it highly likely that her identification of Leaster was inaccurate. Furthermore, after this, Mrs. Whiteside stated that she lost the certainty that Leaster was the attacker.

On top of this, as soon as Leaster was arrested, he was tested for gunpowder residue on his hands. Seeing as the attacker had fired a gun not long before Leaster’s arrest, Leaster should have had gunpowder residue on his hands, had he been the attacker. He did not.

Moreover, a watch was found at the scene of the crime, left there by the attackers in their haste to flee. Leaster’s watch was still on his wrist at the time of his arrest. Leaster wore clothes that matched the description but had no bruises, which the described attacker would have had after being hit with the coffee mug.

Additionally, Leaster had an alibi on the day of his arrest. He had been out in the city getting cigarettes for his girlfriend, whom he lived with. However, his girlfriend was white, and he was black. They already faced enough difficulty as an interracial couple without the presence of police; the police certainly only made matters worse.

After Leaster provided his girlfriend as an alibi to the cops, they went to his girlfriend’s house and berated her for being with a black man. They demeaned her and Leaster’s relationship, asking the girlfriend “what she was doing with that n-word,” as Muse explained. Eventually, the pressure from the police became too much, and Leaster’s girlfriend succumbed to her fear and lied to the police about Leaster, saying she had not seen him in days.

Despite all of the signs pointing to his innocence, Leaster was taken to court. At this point in time, the death penalty was still legal and active in Massachusetts. Leaster’s trial was not only to decide whether or not he was guilty of a murder he did not commit–it was to decide whether or not he would receive the death penalty for it.

During the trial, one woman who had been in the store the day of the attack testified. She had initially claimed that she had not seen the attackers. But when she took the stand, she changed her story and promptly identified Leaster as the culprit.

To make matters worse, Leaster’s lawyer did nothing to help Leaster’s case. The lawyer had never tried a murder case before and, according to Muse and Leaster, he did not know what to do.

In the end, the faulty testimonies and circumstantial evidence won the jury, and Leaster was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison. It was not until six to seven years later that Chris Muse, fresh out of law school, and his father Robert Muse, also an attorney, found Leaster’s case and decided they needed to take action. It took nine and a half years of tireless work to set Leaster free.

“People always ask, ‘You didn’t get paid?’” shared Muse. “Yeah. But we didn’t miss a meal, so it doesn’t make a difference.”

To the Muses, every ounce of effort was entirely worth it. “Out of all the bad things that happened in [Leaster’s] life and all the work my family put in… we have a reward: this man right here, and the story he’s going to tell you,” Muse said with a smile, clapping Leaster on the shoulder.

After Muse’s words, Bobby Joe Leaster approached the podium to share his own experiences. Leaster told the audience that, growing up, he had gone to an all-black school in Mississippi and received a basketball scholarship to Jackson State. But Leaster turned down this scholarship in order to take the opportunity to go to Boston where some of his family lived. So, in 1969, at the age of 18, Leaster headed to Boston. The following year, however, “that’s when my life took a turn for the worse.”

Leaster spoke mostly of his experience following his conviction, as the situation surrounding the crime itself was covered mostly by Muse previously. Leaster talked about the way his conviction affected him personally, as well as the ways in which it affected his loved ones. “[My family was] devastated. They couldn’t believe it,” he shared sadly.

Leaster described his prison life, including the fateful ride to the prison itself–a ride that Leaster, having been sentenced to life, thought would be his last moments spent outside of prison walls.

“One of the guards told me, ‘Bobby Joe, take a good look at this city, because it’s the last time you’re going to see it,’” recalled Leaster. “‘You’ll probably die in this place.’”

From this point on, prison life was not great for Leaster, and Leaster spoke of the hopelessness he felt while locked up despite his innocence. Within his few months at the prison, he got into a fight with a fellow inmate and was later stabbed three times in the back in an act of retaliation.

“I lost a lot of blood,” Leaster shared. “As I lay in my own blood, I’m praying to God, ‘If this is the way I’m going to go, 19-years-old for a murder I didn’t do, in prison for only three months… Take me. Even though you know I did nothing, just take me.’”

In prison, everyone was aware that Leaster was innocent. Many of the inmates actually knew the true culprits of the crime Leaster was arrested for because the robbers were no first-time offenders. It seemed as if everyone knew the truth, yet nothing was being done to honor it.

Finally, after years of being in prison, two lawyers noticed the injustice of Leaster’s case and decided to take it on–the Muses. At that point, Leaster had been imprisoned for six years. He said he saw the Muses as “a gift from God” in his time of need. “I love the Muses. They [are] like my family,” he continued.

Leaster remembered walking into a room with Muse and desperately declaring that he was innocent, and was shocked when Muse immediately believed him–especially because so many others never had.

Following the first meeting between Leaster and the Muses, the next nine years were spent fighting for Leaster’s freedom. Although there were no major successes for quite a while, neither Leaster nor the Muses gave up hope. Finally, in 1986, the tides turned in Leaster’s favor.

For many of the years the Muses worked on Leaster’s case, there was information Leaster either would not or could not share, due to his inability to remember some of the facts. The Muses knew there was information that Leaster was unable to divulge, so they turned to a rather unconventional method at the time: hypnosis.

The type of hypnosis used in investigative settings helps put an individual back into the mindset of a time or experience that information is missing from. By setting the scene and allowing the individual to truly feel like he or she is back to the time of his or her experience, he or she is able to recall certain facts that he or she otherwise forgot or repressed. Through hypnosis, Leaster was able to remember that many of his fellow inmates knew of his innocence and that they knew the true perpetrators. He even muttered the name of an inmate who had given him that information.

With this name, the Muses tracked the inmate. The inmate did not provide the Muses with the names of the attackers outright, but he gave clues that the Muses were able to work with. These clues brought the Muses to the names of Kelsey Reed and Peter Gardner, men who had been arrested for other armed robberies and who possessed a gun that the Muses believed matched the one used to murder Levi Whiteside. However, either man was ever tried, and they both died violent deaths.

But, in 1986, The Boston Globe released an article about Leaster and his story. Mark Johnson, a Boston school teacher, read the article and saw Leaster’s photo. Johnson, at age 13, had witnessed the shooting and knew that Leaster was not one of the three men (although only two were identified) that he saw flee the scene. Johnson immediately called the Muses to inform them of this.

Johnson’s call enabled the Muses to gain access to the bullet fired into Levi Whiteside and confirm that the bullet did indeed match the gun owned by Reed and Gardner. Johnson’s call allowed the Muses to get a new trial for Leaster. Leaster was, in turn, released–sixteen years after the initial crime, Leaster was free.

Leaster talked about the day he was granted his freedom with a wide smile on his face. “I came downstairs and [the Muses] were smiling and they had a paper in their hand. I just felt that it was my freedom.”

Shortly after, Muse helped Leaster secure a construction job in Boston. After four years there, Leaster landed a street worker job. He was told, due to his past, that the job would only last two years. Yet, lo and behold, Leaster has now had his job there for twenty-eight years. He has spent his time as a street worker helping teenagers caught up in gangs and gun violence.

“I’ve been to way over 900 funerals… way over 900,” Leaster revealed morosely. The first funeral he ever attended was for a 14-year-old girl killed due to violence in the streets of Boston. He has guarded the caskets of many other funerals to prevent anyone from reaching into the casket and doing or taking anything.

Despite the obvious pain caused by seeing such violence and loss, Leaster finds his job highly rewarding. He explained that some of the people he helped as teenagers are now police because of him, because they wanted to do better. “They come up to me and say, ‘You changed my life,’” Leaster reminisced

Even though Leaster certainly suffered a great deal throughout his life, he seemed to only look back happily. When asked by a student if Leaster regretted choosing not to go to college and instead to go to Boston, Leaster replied, “No. This might sound weird, but… I grew up inside the institution.”

Having been imprisoned at such a young age, Leaster explained, he was shaped by the system. Because of the system, he met the Muses. Today, he has a 30-year-old son and many friends he may not have had otherwise. So, although he was deeply wronged, he does not regret the way his life turned out.

“I think what I have now is better than what might’ve been,” Leaster commented thoughtfully. “I really like my life here.”

“I was really moved by the idea of how positive he was and how his outlook on life hasn’t changed,” commented junior Lizzie Jacobson in regards to these remarks made by Leaster.

Senior Aidan Sandler agreed. “Bobby Joe is a good man,” he reflected.

After this, Muse’s niece asked how the system differs today in comparison to the time of Leaster’s conviction in the opinions of Muse and Leaster. Both affirmed that there have been many, many changes in all areas. “Back then, they didn’t have DNA or nothing–now they got all kinds of stuff,” Leaster elucidated.

“Now, it’s hard to get convicted when there are lawyers like the Muses,” he added with a playful smile.

Ms. Roth, an English teacher, then asked Leaster and Muse about the changes in the system on a more social level, including those caused by the roles played by social media and racially-biased policing in the legal system today.

“I think it got a whole lot better,” Leaster shared of his experience as a black man wrongfully imprisoned largely because of racial bias and profiling.

Muse added on, stating that there are certainly more women and people of color working for and representing minority groups in the system and being more fairly treated by it in many cases, but prejudice remains oppressively prominent in the system today. Muse spoke of the progress being “not enough, but still there.”

Muse then addressed the students in regards to prejudice in today’s society and the importance of recognizing personal biases in order to overcome them and make progress as a community. Although it is hard to recognize, it is crucial to acknowledge the prejudices that so many people inherently hold in order to fix them. Muse advised the students before him to “consider yourself lucky, not better” in regards to privilege.

“You don’t have the hateful, scornful prejudice that [Leaster] lived with but there’s still a lot of prejudice out there. It’s important that you know that,” Muse elaborated.

Muse then turned back to Leaster, saying that, while it is great that Leaster is happy with his own life now, it is very important to know all of the amazing things Leaster has done to better lives other than his own as well.

Because of Leaster’s case, Massachusetts legislators have voted against reinstating the death penalty, often specifically pointing to the fact that Leaster was almost sentenced to death as an innocent man. Today, the death penalty has been abolished in Massachusetts since 1982. In response to Leaster’s case, numerous general laws in Massachusetts have changed. The courageous fight that Leaster put up for his rights generated real progress and positive outcome.

At the conclusion of the speeches, Muse and Leaster encouraged all of the students to pick up some pocket versions of the Constitution and Declaration of Independence, reiterating the importance of all people knowing their rights and being given fair and equal treatment before the law and in all areas of society.

Together, Muse and Leaster shared a story that spoke volumes to the dire need for equality in this country and this world, as well as the great victories that can be achieved when people from all walks of life work together to attain it. Muse and Leaster emphasized the importance of intersectional equality before the law and throughout society, a message that will hopefully resonate with each and every HHS student and staff member. The Chronicle

The Chronicle

Ival Kovner, Bethel, Connecticut • May 11, 2020 at 10:05 am

My husband, Attorney Ronald Kovner and I share the sad news that Bobby Joe passed away on 4/26/20 due to injuries sustained in a house fire.

We both remember vividly the day Bobby Joe was released from prison. For years the Muse firm had worked pro bono in support of this innocent man..Brigham & Women Hospital has a fund for artificial

skin research under Dr. Dennis Orgill – hopefully still there – we know the hospital offers burn care. Bobby Joe will always be close to our hearts. He gave to the community without fail – his faith lights the way knoeing his trust in truth. With the memorial service postponed due to the current pandemic, our prayers fill the time in the interim.May his memory be for a blessing.