History is Human: An Interview with writer and historian David McCullough

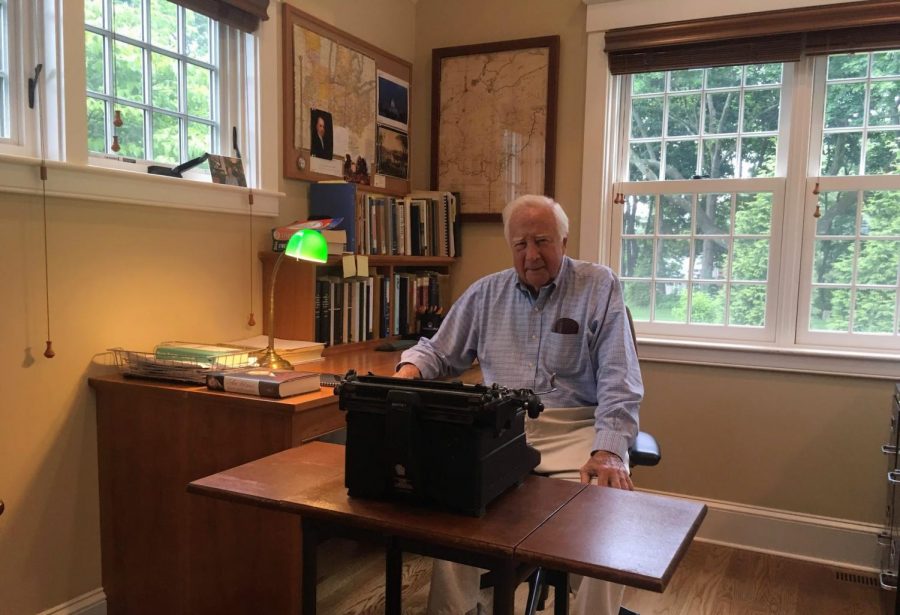

David McCullough sitting at his typewriter.

September 30, 2018

Leaning back in a rocking chair on his white wooden porch, David McCullough admires his yard as it flourishes in green. He points to “his office,” a small, white house across the lawn that him and his son built together. Inside, a model of the David McCullough Bridge in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, stands proudly before the office space. Next to the wall filled completely by bookshelves, portraits, maps, and photographs hang. Tables covered in mail include a special basket reserved for “fan mail.” In the center of the room rests the object of creativity: his typewriter. He loves good mystery novels and painting, yet he is no ordinary resident of Hingham. David McCullough is a two-time Pulitzer Prize winning writer and historian, his work has been translated into nineteen different languages, and he just so happens to reside down the street from Hingham High School.

Mr. McCullough describes himself foremost as someone who always loved to read and to be read to. At Yale University, he earned a B.A in English. He recalled, “I was an English major and I wanted to pursue that. I thought I would be a writer, and imagined myself writing newspapers, magazines, or novels, or plays, but writing history had never entered my mind.”

After college, Mr. McCullough worked in New York City for Life and Time magazines. At this time, John F. Kennedy was running for President of the United States. Mr. McCullough explained, “I was very enthusiastic for his candidacy, and when he won and gave his inaugural speech, calling on the country, particularly our generation to do something for our country, so I quit my job and I went down to Washington. I knew nobody in the Kennedy campaign crowd, and I knew nobody in government. And I went door to door hoping to find a job where I could use my education and experience up to that point to serve the country.”

In the District of Columbia, his first true interest in writing history sparked while browsing the Library of Congress: “One day I saw a set of photographs that had been sitting out on a table waiting to be filed that had been taken in Johnstown, Pennsylvania after the disastrous flood in 1889. I’d grown up in Pittsburgh and I had heard about the Johnstown flood but I didn’t really know how severe the tragedy was. The photographs showed a devastation such that I never imagined and I was curious: how did it happen? How extensive was this tragedy? So I took a book out of the library to read about it and the book wasn’t very good. So I took another book out of the library and it was even less satisfactory, mostly made up. So I thought, ‘why don’t you make a book that you’d be able to read?’ And that’s what I did, and that’s what I’ve been doing ever since.”

Since then, Mr. McCullough has published books covering every inch of American history, from the Revolutionary War to the building of the Brooklyn Bridge to the Arcadia Conference of 1941. How did he choose the subjects for his research? Mr. McCullough described, “If I knew a lot about a subject, I wouldn’t want to write about it… There’d be no discovery. None of the excitement of being on the hunt, of being on the detective case.”

His most famous biographies examine the lives of Americans such as John Adams, Teddy Roosevelt, the Wright Brothers, and Harry Truman. “I like to write about people whom I feel have been too long in the shadows. Bring them out because they’re interesting, or important, or they’re human.”

Currently, Mr. McCullough is working on his twelfth book, 50 years after The Johnstown Flood was first published. When asked which of his twelve books was his favorite to write, he replied frankly, “My favorite book to write is the one I’m working on. Always. I get completely focused, completely absorbed in what I’m trying to put down on paper.”

His twelfth book focuses on the first settlers of the Northwest Territory who began their quest from Hamilton, Massachusetts, in December of 1787. Entering unexplored territory, the forty seven men traveled without access to bridges, roads, or towns, only equipped with minimal tools and clothing. Mr. McCullough elaborated on his research for this book: “I’ve been trying to track down each of them, find out what I can, what was their profession. Some were surveyors some carpenters, some were just strong young men. Lo and behold, I just found that one of them came from Hingham! His name is Samuel Chase and we found him down at the Hingham Historical Society where they are [now] trying to track down exactly who Samuel Chase was. I know he was young, and the name Chase appears in a number of ways here in Hingham. So you never know what you’re going to find, and it might turn up to be right in your own backyard.”

Research, such as what was done at the Hingham Historical Society, is a vital, time consuming part of historical writing. Mr. McCullough spoke,“There’s a kick that comes with the research. I’m often asked, ‘how much time do I spend writing?’ And, ‘how much time I spend doing research?’ No one ever asks me how much time I spend thinking. And the thinking is often the most important part of it. And I don’t think the general reader really knows how much work goes into a book. It’s hard work.”

Concerning his book Truman, which was awarded a Pulitzer Prize in Biography and Autobiography in 1993, he shared, “I think my years as a journalist schooled me to go about that [research] in a different way from many academics, because I don’t just use manuscripts or diaries, or record books or all that, I use newspapers a lot. I use photographs a lot. I always go to the place that things happened and smell the air, and listen to how people talk; I think it’s essential. In case of the Truman book, I interviewed well over one hundred people for that book because there were so many who were still living who could talk about it.”

Regarding the writing process, Mr. McCullough expressed his love for The Elements of Style by Strunk White. “Best book on writing ever written. I do a little reading of it every now and then just to remind myself… the hardest thing to learn is to edit yourself. Don’t just write: write and rewrite. I believe very strongly that one should write for the ear as well as the eye and that is a great importance to have what you’ve written read aloud to you because you hear when you are using the same word too often, or you hear when your sentence structure is too repetitive, and I think more important than anything, you hear when you’re being boring.”

Mr. McCullough’s book 1776, published in 2005 and named the American Compass Best Book of 2005, is formatted unlike any other non-fiction literature on the Revolutionary War. The size of the “illustrated version” of 1776 is comparable to that of a large children’s book. With accompanying text on one page, a pouch fills every second page. Inside these pouches are replicas of documents such as Abigail Adams’ letter to John Adams or George Washington’s Map of Boston that readers can hold in their hands and observe for themselves.

Emphasizing how 1776 contrasts his other works, Mr. McCullough explained, “1776 is what I’d call pure narrative… I like to write about people who don’t give up. They undertake a big objective, a big project a big goal, a seemingly impossible goal, and they blunder, they make mistakes but they don’t give up and they learn from their mistakes. They don’t whimper and whine and walk off lying there. They pick themselves up, dust themselves off, figure out what went wrong, try to fix it and keep going. And that’s what 1776 to a large extent is about.” When asked if he picked which documents were included in each pouch, he proudly stated, “there is no illustration, no photograph, no map, no anything in my books that I didn’t choose, or that I didn’t find and bring to the publisher. And I wrote all the captions. Always.”

In a world that increasingly stresses the importance of STEM education, Mr. McCullough expressed the value he sees in a humanities education, which reaches far beyond the classroom. “I think that every student in school from grade school right on through should be learning, reading, and involved with the quest of learning that comes through learning history. In many ways, the most important subject that education provides,” Mr. McCullough explained. “I think that a knowledge of history is essential to leadership. Anyone that anticipates in playing any part in being a leader, should absolutely take it. Harry Truman was the only president of our time who never went to college. He was an avid reader of history his whole life and it benefited him enormously. The best presidents we have had have been leaders of history.”

A particular interpretation of history, avidly used both by various historians in everyday conversation about global politics reads, “history repeats itself.” To whether or not he agrees with this philosophy, Mr. McCullough replied simply, “No. Several things I don’t believe. There’s no foreseeable future, there never was, and that’s one of the lessons of history, and there’s no such thing as a self-made man or woman. We’re all results of lots of people who shaped us. Primarily teachers, other than your parents, great teachers, can change your life. I don’t think history is just about politics or the military. It’s about people, and art and music and architecture and science… History is human. I think that’s the most important part.”

To beginner writers attempting to pursue research, Mr. McCullough advised, “Don’t act like you know because you’re not there yet… it’s not a one man show ever. Efforts of any importance or value are always joint efforts. And I think that’s a lesson in life and a lesson in history that ought to be drummed into everybody. You’ll do a better job if you have someone good working with you… And when I first started out I thought you do all the research and then write the book. That’s not the way I work because as you proceed you accumulate more knowledge, because what you know towards the end of the book about what happens in the first part of the book is far more than when you wrote the first part of the book. So it’s best from what I’ve found to get enough research to get started, get started, and keep on researching all the way along. That, for me, has worked really well.”

David McCullough then resumed to explain the process of “sharpening, sandpapering, and garnishing” his twelfth book before briefly interrupting himself to point out a bunny rabbit hopping across the grass. As the bunny reached the bushes, he smiled and said, “I’ve had a wonderful time. I love my work.”

As Mr. McCullough continues to pursue his work at age eighty-five, he reminds young people that history is, in fact, human through his appearances at colleges across America. Specifically, he has taught a writing course at Wesleyan University in Connecticut and is a visiting scholar at Dartmouth College and Cornell University. Locally, he extends his wisdom to the community through meeting with Hingham High School teachers and participating in public events at the Hingham Historical Society. He remarked that he is proud that ten of his descendants, including children and grandchildren, have all graduated from the Hingham Public Schools system.

Principal Swanson • Oct 25, 2018 at 8:32 am

I loved reading Claire Taylor’s profile of our school’s most famous neighbor! In my opinion, David McCullough deserves the title so often bestowed upon him: “America’s Greatest Living Historian.” He is a national treasure, and his books represent an enormous gift to anyone who wishes to understand the history of our country. This Harborlight feature belongs in a “Greatest Hits” compilation of our school newspaper’s most memorable columns. Every HHS student should read it…and (heeding some of Mr. McCullough’s most important advice) THINK about it!”

Lindsay O'Neil • Oct 3, 2018 at 11:14 am

Claire, this was a fabulous interview. As someone who is interested in history and the possibility of a career in the field, I found this article very insightful. I had no idea that the town of Hingham was home to such an extraordinary man! Nice work and I’m looking forward to your next article.