Letter to the Editors: Why You Might Be Wrong About the Trolley Problem

Delft University of Technology

Philosophers have puzzled over the Trolley Problem for decades, and even today it continues to inspire fresh debate.

January 25, 2021

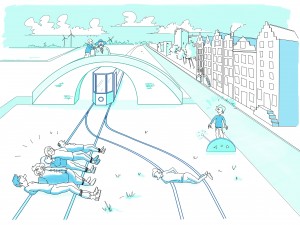

A trolley is hurtling down the railroad tracks, unstoppable. On the tracks stand five construction workers who are unaware of the trolley headed straight towards them. You see this happening, and of course want to intervene, but wait! You can switch the course of the train on to a new track by pulling a lever right next to you. If you do this, you should know, there is just one construction worker on the other track that you’d be killing. So, what’s the solution; do you pull the lever? Studies show that ninety percent of people would decide to kill just one person, so I’m going to go out on a limb and say you, yes you, probably fall into that category. Now allow me to change your mind, because, respectfully, you are wrong.

What if it was your brother or sister? Your mother? Your best friend? Does your answer change? I’d hope so. And that’s why utilitarianism doesn’t work. Utilitarianism is the belief that any action would be considered “morally right” if it benefits the majority. No matter the situation, no matter who the “majority” might be, you have to save the greatest number of lives. Therefore you pull the lever. But this line of reasoning creates unemotional, distant beings that disregard anything that isn’t a statistic. It’s impossible to detach yourself from the implications your actions have on you; after all, that’s what defines us. So, if you’re just going to pull the lever without thinking twice, what does that say about you. According to math, five is greater than one, obviously, but according to philosophy, murdering is always wrong. Utilitarians would argue that, even if it’s your mother, you should kill her to save the five. No questions asked. That’s no way to go about life; we have feelings, emotions, and complex brains that can think beyond just what the numbers represent. Deontological ethics align with this kind of thought. It’s the theory that the morality of an action should be based on whether or not said action itself is “right”, rather than what its consequences may be. Each decision you make should be judged separately from the last, and it is your responsibility to weigh the morality of your actions. You can’t just make it a number game, it forces self-reflection and accountability. Let’s take it back to the trolley problem. You either let five people die or kill one; quick, weigh your choices! Okay, so if you’re like me, then you reached the same conclusion you did before: kill the one. But we had to think about it. Time for the second version. Your mom is standing on that second track: quick, weigh your choices! Now I’ve changed my mind, it is my duty as her daughter to protect my mother. I’m not pulling the lever. Did you agree? If so, you’re not a utilitarian, welcome to the club. Trust me, it’s better on the other side.

I’ve got another thought experiment for you, not surprisingly, involving a trolley hurtling down some tracks. But this time, the trolley is passing under a bridge that you and some random guy are walking across. If you do nothing and watch from the bridge, the trolley will continue on its track and kill five people. But, you could choose to push the other guy off the bridge, effectively stopping the trolley from moving, but killing him. What’s your plan of action? When asked about this version of the thought experiment, most people decided not to kill the random man on the bridge. Why though? It’s the same principle: kill one to save five. If you find yourself in the majority here, choosing to kill one person in the original version but refusing to push the man off the bridge now, then you’re a fraud. Or rather, you’re an existentialist, but who’s to say. Existentialists weigh their actions based on how it makes them feel, and how it reflects on them. By pulling the lever, you’re a hero because you just saved five lives. The lever is detached enough from any personal responsibility. But pushing a man off a bridge? That’s straight-up murder and therefore is a no-no. Most of philosophy is just providing differing contexts. It’s about how you got to the answer, and why you decided to pull the lever. If you did it because the numbers played out, that’s amoral, and if you did it because it makes you feel better, that’s amoral. You should be doing it because the action itself is moral. The “one size fits all” of ethics is deontology. It always will bring you to a moral decision.

I hope you’ve changed your mind and seen the other side. You can still think it’s right to pull the lever, of course. But you need to know why. The implications of all this are much greater than who dies in a metaphorical thought experiment. Setting a moral code for yourself is essential; we need individual standards to abide by or else we all become savages, doing what we want, when we want, no matter whom it hurts. And if you don’t believe in any of that and you just want to go on and live your life, think about that next time you need a favor. Without morality and the will to do good, we’d all be individuals surviving alone in the world. That’s why we all need to choose deontological ethics: to simply be good people.